The Justice, The Journalist & the Judgment of History

Everyone is talking about the Supreme Court’s big Indian Law decision. But here’s what’s missing from the conversation: Black People

The United States Supreme Court ruled last week that much of eastern Oklahoma falls within the Muscogee (Creek) Indian reservation.

The 5–4 decision, in McGirt v. Oklahoma is perhaps the significant legal victory for Native Americans in a generation. It will have broad implications for Native people who live across Indian Country, including what the Court affirmed as Native American land in Oklahoma’s second-biggest city, Tulsa.

More on Tulsa, in a moment.

But first, the case. McGirt v. Oklahoma is rooted in our country’s sordid history of violent removal and broken treaties with the people who lived here first — the Indigenous tribes. Neil Gorsuch, one of the Supreme Court’s most conservative Justices and a letter of the law textualist, wrote the Court’s opinion:

“On the far end of the Trail of Tears was a promise,” he began. “Forced to leave their ancestral lands in Georgia and Alabama, the Creek Nation received assurances that their new lands in the West would be secure forever.”

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation is one of the so-called 5 Civilized Trbes. The Creek is a self-governed tribe based in Okmulgee, Oklahoma and is the fourth largest tribe in the United States, with as many as 86,000 citizens.

The federal government forcibly removed these 5 tribes from their native homelands in the southeastern states. The Cherokee, Muskogee, Seminole, Choctaw, and Chickasaw covered the Old South, from Florida through North Carolina then westward into Mississippi and Arkansas.

As Indian law cases go, the issue in McGirt v. Oklahoma was a simple one:

Did the native land of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation remain a reservation even after Oklahoma became a state.

The answer: Yes.

Supreme Court reasoned that Congress never adopted a single law or statute to cancel, terminate, or supersede the treaty.

“Because Congress has not said otherwise,” Justice Gorsuch wrote, “we hold the government to its word.”

The Court’s decision is a remarkable and overdue affirmation of this country’s obligations to Indigenous people. Together with the four liberal Justices, Justice Gorsuch recognized the largest tract tribal land in the contiguous United States, some 19 million acres encompassing the entire eastern half of Oklahoma, including a good swath of Tulsa, as reserved to the Creek Nation.

Yet, the celebratory conversation many of us have been having around this milestone case fails to appreciate the ways in which our federal government’s vicious removal policies toward the Native Americans intersect with the other original American sin — chattel slavery.

My great grandmother Ollie Brown, my father’s grandmother, on his mother’s side was from Gary, Indiana, by way of Tulsa, Oklahoma. She was born in Madison, Georgia in 1871, just in time to taste the promise of Reconstruction.

As family lore passed it down, Ollie was part Choctaw and part African American, a blended identity that may seem unlikely in the fairytale version of Oklahoma spun by Rodgers & Hammerstein. But if you know the true history of the Sooner State, it makes perfect sense.

White settlers filtering into the southern territories in the 17th century made a deal with the Indigenous people of there: if you really want to assimilate you need to (1) stop hunting in favor of agriculture and grazing, and (2) embrace white supremacy, which included keeping African people enslaved. And they did.

If we are honest about it, they are known as the, 5 “Civilized” Tribes because they agreed, back in the day, to inculcate Anglo-American norms — the adoption of European agricultural, political, and religious institutions. They participated in the market economy. Eventually, they married whites and adopted patrilineal descent.

This designation, “civilized,” distinguished these five tribes from other so-called “wild” Indians who continued to rely on hunting for survival and retained the Indigenous culture, religion, and tradition.

But, the 5 Tribes were also viewed as civilized because they agreed to adopt slavery. This was the deal they made with the devil.

Despite the deal, of course, the federal government tragically and brutally removed the nations from the southern states, in the 1830s and 1840s. Still, the Native Americans did not free their enslaved people. Instead, the African Americans were also removed under the same harsh conditions. The Cherokee had the largest number, with more than 1500 enslaved Blacks living and toiling on Indigenous land. The removal resulted in approximately 300 enslaved African Americans in the Creek Nation to more than 1200 in the Chickasaw Nation removed with the other nations. By the time the Civil War erupted in 1861, the 5 Tribes enslaved between 8,000 to 10,000 African Americans, comprising approximately 14 percent of their population.

But the tragic irony of this imposed “civilization” does not end there.

The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 officially outlawed slavery, but it did not end slavery within the cultural confines of the 5 tribes. General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate troops at Appomattox, on April 9, 1865, but slavery was not over. Another month would pass before Union army general Gordon Granger announced, in Galveston, the federal proclamation that all enslaved people in the state of Texas were free. (That is why we celebrate Juneteenth.)

But even after that, there were still thousands of enslaved people toiling away in Indian Country, and they were not freed until 1866.

At the end of the Civil War, the federal government negotiated with each of the 5 Tribes to reduce their reserved land. The federal government allotted to each tribal citizen just 160 acres. But the treaties also required the tribes to free any enslaved people living on tribal lands. And the federal government gave each Freedman 160 acres, too.

In truth, it was hardscrabble land nobody much wanted. So the bargain, at first, was a good one for the federal government and a poor one for the Indians and Blacks making do with their 160-acre parcels.

But there was one thing the government didn’t count on: oil.

After President Theodore Roosevelt signed the proclamation establishing Oklahoma as the nation’s 46th state in 1907, seemingly bottomless pools of oil were discovered underground near Tulsa, making Indian Country — and the plots the Freedmen held — valuable beyond measure.

The descendants of formerly enslaved people, from Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, and beyond, flooded into the state, hoping to make their fortunes. A vibrant and vital self-contained economy soon arose. But ironically, too, segregation gave rise to a nationally renowned dynamic black entrepreneurial center.

It was the Greenwood District. It was named for its Greenwood Avenue which ran north for a mile to the Frisco Rail Yards and was only one of a few streets in town that didn’t cross through both white and black communities.

Greenwood has long been known as, “The Black Wall Street,” a beacon for southern Blacks like my great grandmother, Ollie.

“The slave went free, stood a brief moment in the sun and then moved back again toward slavery.” — W.E.B Dubois, 1935

W.E.B. Dubois was writing about the larger failures of Reconstruction, but he could have been talking specifically about Greenwood — a fleeting moment for African Americans to live the American Dream: shops and hotels, two movie theaters, two schools, 13 churches, a public library, even a roller-skating rink, all Black-owned. Perhaps most significantly there was The Tulsa Star.

Andrew J. Smitherman founded The Tulsa Star on the cusp of the Great Migration. It was the longest-running daily in Oklahoma, owned and operated by a Black publisher and its printing press was in Greenwood.

This thriving district, in the middle of entirely white Tulsa, which had been Indian Country just twenty years before and still straddled the Creek Nation, was a boomtown that welcomed all Tulsans willing to visit or do business: white people for music, dance and entertainment; Jewish merchants setting up shop; and Native Americans trading or visiting family. The surrounding white bible belt in Tulsa became increasingly resentful of the prosperity and race-mixing in Greenwood and thereby adamant about reinforcing white supremacy.

As Oklahoma became more like the rest of the south — as segregation took hold, as lynching became part of the culture, as false reports were made against black men for raping white women, Smitherman and his Tulsa Star denounced all of it. On his editorial pages, he called upon African Americans to prepare to defend themselves, by any means necessary.

But he had a rival across town.

In Tulsa, The Tulsa Tribune owned by white nationalist Richard Lloyd Jones, whipped up anti-Black sentiment, calling Greenwood, “Little Africa,” creating a loathing for the new music called jazz and ginning up fear around the new prosperity African Americans enjoyed. The Tulsa World denounced the new equality African Americans were beginning to feel as part of their free status. Most of all, he stoked fear among whites about their lost position in Oklahoman society and America.

“If something isn’t done,” Jones wrote in an op-ed “Something is going to explode.” And explode it did.

19year-old Dick Rowland worked in the Drexel building, shining shoes. On Memorial Day, 1921, Rowland, who was Black stepped into the elevator to ride up to the segregated bathroom, located on the top floor. In the elevator cab sat Sarah Page, a 17-year-old elevator operator who was white. Precisely what happened on the elevator has never been clear. The Tulsa Star reported the allegation of attempted rape, though Sarah Page never pressed charges and there was no evidence to indict or convict Rowland. Still, after years of stoking white resentment and fear in Tulsa towards their Black neighbors in Greenwood, the stage for violence had been set. The Tribune’s front page screamed, “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in An Elevator.” That headline tripped the trigger for the worst racial massacre in our nation’s history.

White men stormed first to the county jail where Dick Rowland was in custody. But they were met not only by armed African Americans there to protect the boy, but also the white Sheriff and his Black deputy wanting to forestall a firefight. The mob moved on.[1]

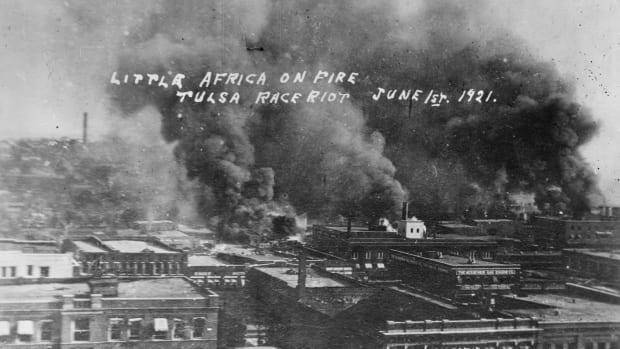

Over the course of the next sixteen hours, white Tulsans waged war on their Black neighbors, with thousands of white men setting upon Greenwood, determined to destroy this symbol of African American prosperity and independence.

Bi-planes flew overhead, dropping Molotov cocktails on stores, schools, homes, and churches below. Tulsa’s police chief, John Gustafson, deputized whites who were on the rampage. He even handed even out badges. Soon the National Guard arrived, but not to protect the citizens of Greenwood. Instead, the Guard shared its water-cooled Browning machine gun with the white mob to aid in the attack.

But this was the wild west and Greenwood was not taking it lying down.

African Americans were vastly outnumbered, but they were also well-armed and took up the fight. The men assumed defensive positions around Greenwood, as women, children and babies fled their homes.

But African Americans were rounded up by law enforcement and sent to internment camps. By midmorning, fires were burning from the bombs dropped overhead. And many were just shot dead on the Black Wall Street they had built — some shot and killed on their front porch, in their yard, in their homes.

Presaging…

Eleanor Bumpers

Amadou Diallo

Renisha McBride

Botham John

Breonna Taylor

Most experts of the Tulsa Massacre say at least 150, and more likely hundreds of Black people were murdered in those few short hours,[2] killed by a white mob outraged over their exercise of economic independence and freedom. [3]

Hundreds dead.

An entire neighborhood and community wiped out.

Yet, no one has ever been prosecuted. No restitution has been paid. No one was ever convicted of any crime.

Nor is the story taught in our schools, not even in Oklahoma.

George Floyd was also murdered on Memorial Day, ninety-nine years to the day, after the massacre in Tulsa.[4]

After weeks of protests across our American cities, in the words of Dr. King, Where do we go from here?

For a short and shining time, Greenwood flourished. Despite Jim Crow. Before the rampage. Then, in a matter of hours, millions of dollars in hard-earned wealth — property, homes, businesses, investments — were burned to the ground. Ten thousand Black people were left homeless, with 1,200 homes and scores of businesses, all destroyed.

For African American descendants of Greenwood, the massacre isn’t just history — it is felt to this day.

Most of the survivors never recovered financially. Instead of inheriting Black Wall Street’s wealth, survivors and their descendants have inherited diminished economic opportunity, unequal educational and healthcare outcomes, and increased interactions with law enforcement — not to mention a century of obstruction from the city of Tulsa and the state of Oklahoma.

Lessie Benningfield Randle is the last known survivor of the massacre. Over the decades, Tulsa should have made amends to Ms. Randle and to the Randle family. When she turned 105 last year, Lessie Randle said she wanted only one thing for her birthday: the restoration of her run-down home. Yet, Tulsa did nothing.

Randle’s ramshackle old house is a metaphor for Tulsa’s broken relationship with its African American citizens and reflects its unwillingness to accept responsibility for the massacre and its refusal to honor to its victims. (Prominent Black residents of Oklahoma paid to restore Randle’s house.)

In 2000, the Tulsa Race Riot Commission recommended that survivors, descendants and the community of Greenwood be paid reparations. The state refused.

Survivors filed a federal lawsuit in 2003. The case was dismissed in federal court for failing to meet Oklahoma’s two-year statute of limitations. When Greenwood descendants appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, they were not as fortunate as was the Creek Nation. The Court denied their petition.

But that lawsuit did not seek financial payments directly to the survivors or descendants; instead, it asked for educational and health-care resources for descendants who remain in the community. This seems an equitable next step.

While the repressive and violent removal of Native Americans and the enslavement of Americans were the original sins of this nation, this dire legacy has been perpetuated and compounded by other sins, which continue to this day.

Now that the U.S. Supreme Court has properly recognized the Indian treaties that honor the reserved lands of the Muskogee (Creek) Nation, it’s time for Oklahoma and the City of Tulsa to continue to unravel the racial injustice of Tulsa’s shameful history by supporting reparations for victims like Lessie Benningfield Randle and the descendants, in the form of educational and health-care resources for those still in Tulsa.

The current protest movement demonstrates that any reforms we institute going forward will not last until we reckon with — and pay for — the crimes of the past.

[1] Prosecutors eventually dropped all charges against Dick Rowland, purportedly at the written request of Sarah Page.

[2] The state commission found 36 died: 26 Blacks, 10 whites. Those numbers were based on contemporary autopsy reports, death certificates and other records. https://archive.org/details/ReportOnTulsaRaceRiotOf1921

[3] AJ Smitherman was one of the main targets of the mob in Greenwood. But he was also protected by his Black friends and neighbors. He fled Oklahoma, effectively exiled. As have many African Americans throughout our history, he made his way to upstate New York and continued courageously to lead a successful career in journalism for an additional thirty-five years.

[4] As an a former criminal defense attorney, I choose the word “murdered” here deliberately. I believe in the presumption of innocence. But I have also watched the video. In Minnesota, “Whoever, …causes the death of another by perpetrating an act eminently dangerous to others and evincing a depraved mind, without regard for human life, is guilty of murder.” This was that.